Upon granting unified accreditation to the University of Maine System in July 2020, our regional accreditor, the New England Commission of Higher Education (NECHE), asked us to prepare a self-study in advance of a Fall 2022 visit by a NECHE-appointed evaluation team. Standard Six: Teaching, Learning and Scholarship can be found on this page.

Faculty and academic staff are vital to the missions of UMS universities and the University of Maine School of Law (Law School). Faculty are hired through shared governance processes and have qualifications appropriate to their roles. A majority of full-time faculty have terminal degrees in their disciplines (74%), and other faculty are also appropriately qualified to teach at a university level.

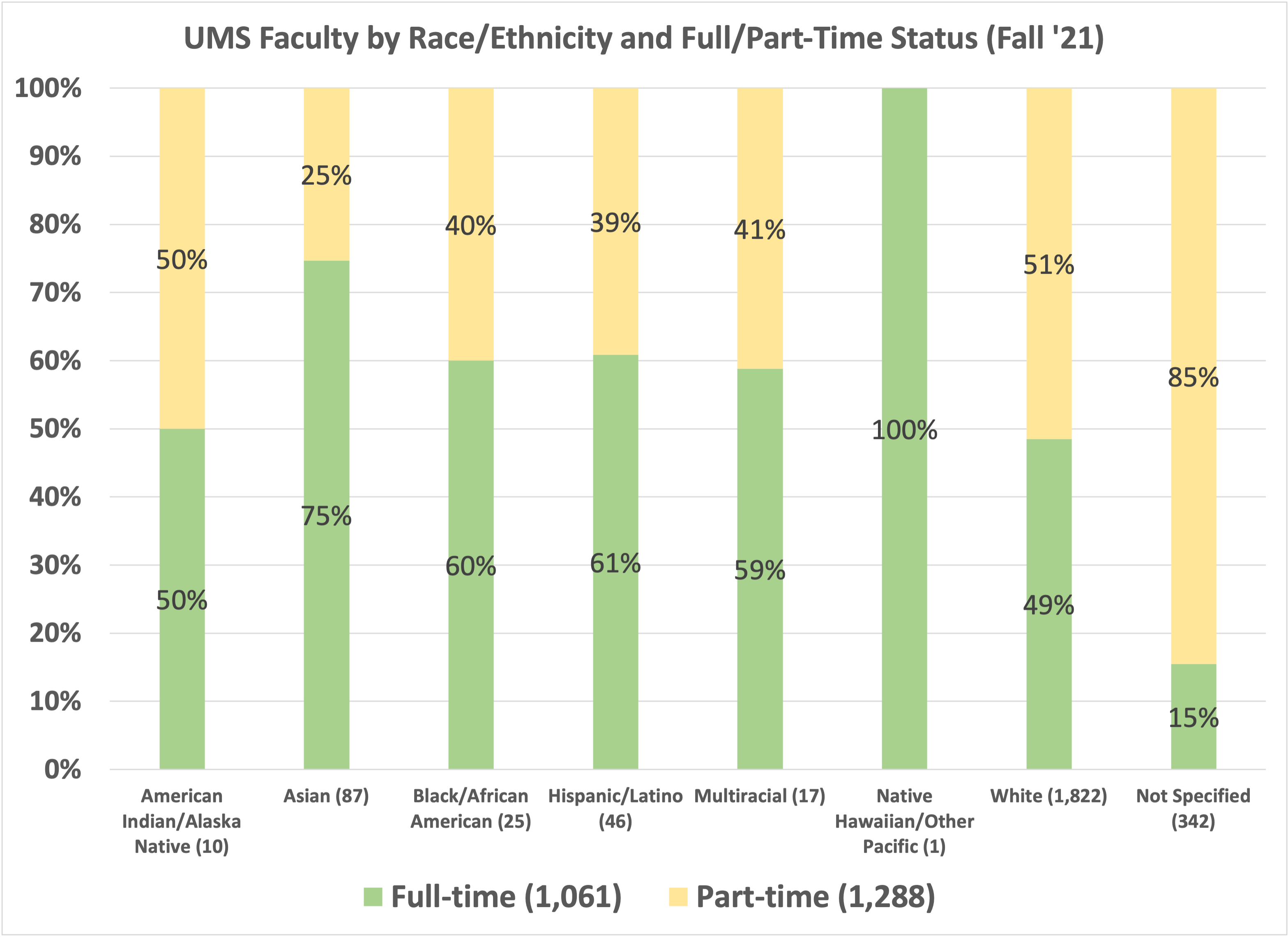

Figure 7: Faculty headcount

| Faculty | Full-time | Part-time | Total Headcount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (1,325) | 519 | 806 | 1,325 |

| Male (979) | 541 | 438 | 979 |

| Not Specified (45) | 1 | 44 | 45 |

| Total | 1,061 | 1,288 | 2,349 |

| Faculty | Full-time | Part-time | Total Headcount |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Asian | 65 | 22 | 87 |

| Black/African American | 15 | 10 | 25 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 28 | 18 | 46 |

| Multiracial | 10 | 7 | 17 |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| White | 884 | 938 | 1,822 |

| Not Specified | 53 | 289 | 342 |

| Total | 1,061 | 1,289 | 2,349 |

Description

Faculty and academic staff

The percentage of full-time and part-time faculty is determined by the mission of each university. Expectations for faculty work and evaluation are established in and described by UMS’s collective bargaining agreements and in university governance documents. Full-time faculty have responsibility for the curriculum. Each university has a faculty governance body that attends to faculty business, with expectations of shared governance. Faculty shared governance is affirmed by Board policy and by the Board’s 2007 Statement on Shared Governance.

As noted in Standard Three, UMS has two faculty collective bargaining agreements: the Affiliated Faculties of the Universities of Maine (AFUM) agreement for full-time faculty, and the Part Time Faculty (AFT-Maine; informally PATFA) agreement. Categories of faculty positions (e.g. part-time, lecturer, research, adjunct, tenure-track, and clinical) and tenure- track ranks (assistant, associate, professor) are defined by the two agreements. They list the ranks full-time and part-time faculty members may achieve, minimum salaries, and review processes. Each faculty member is hired into one or more appropriate academic (degree-granting) or research units via a letter of appointment. The participation of various categories of faculty in unit governance is determined by unit governance documents.

Some professional staff from the UMPSA bargaining unit and non-represented staff teach or mentor students. Academic units determine the qualifications necessary for their teaching staff.

Tenure and promotion

Criteria for reappointment, tenure, promotion, and post-tenure review are determined at the academic program level and are expressed in university governance documents.

The AFUM collective bargaining agreement defines the full-time faculty workload, and that definition is broad enough that it can be interpreted according to university, college, school, or departmental needs. Faculty workloads vary depending on the research expectations of the university and the requirements of the position.

The six-year probationary period for permanent faculty is contractual. Professional development funds are apportioned in accordance with the expectations of the faculty position. The Chief Academic Officers (CAOs) share plans for the hiring of permanent (tenure-track or “just cause” eligible) faculty annually with the Chief Academic Officers Council (CAOC).

The preparation and qualifications of faculty and academic staff are appropriate to the nature of their assignments. Qualifications are measured by advanced degrees held, evidence of scholarship, advanced study, creative activities, and teaching abilities, and relevant professional experience, training, and credentials. Faculty positions generally require a terminal degree, most commonly the Ph.D. or a doctorate other than the Ph.D., but sometimes a terminal master’s degree such as the MFA. Part-time faculty from professional fields are not necessarily required to hold an advanced degree. Part-time faculty and non-faculty academic staff who advise or support students are recruited through a competitive search process.

Search committees for staff members engaged in teaching, learning, advising, and other student support roles are populated by faculty and staff who hold similar roles and are cognizant of mission and needs. As support for all of the above, the universities and Law School receive centralized data and related assistance from UMS Institutional Research. Continuity in teaching and learning is determined in part by reporting lines, with university Academic Affairs and degree-granting academic units holding primary responsibility for instruction and the delivery of student credit hours.

Per UMS Board of Trustees Policy 310, the Board grants tenure to the institution’s faculty. Board Policy 312 provides for the appointment of university professors by the Chancellor with Board approval. Under unified accreditation, this remains in force.

Faculty responsibilities

Faculty assignments range from full-time research to full-time teaching, with many carrying substantial responsibilities for outreach, engagement, and public service. There are an adequate number of faculty and academic staff, including librarians, advisors, and instructional designers, for UMS to carry out its educational mission. Faculty responsibilities include instruction and the systematic understanding of effective teaching and learning processes and outcomes in courses and programs for which they share responsibility.

Additional duties may include student advising, academic planning, and participation in policy-making, course and curricular development, research, and institutional governance. University websites share information about student-faculty ratios and student metrics.

At each university, there are systems in place based on the AFUM agreement to evaluate tenure-track, post-tenure, and adjunct faculty. The Law School is governed by a separate policy. At each university, faculty appointments, tenure and promotion processes, and decisions are reflective of those of peer universities. The evaluation criteria applied in these decisions are developed at each university, but include teaching, student advising, and curriculum development; research and scholarship (e.g. creative works in the discipline, publications and presentations, research, and scholarly writing); and service to the department, college, university, and community.

Per Board Policy 313, each university in UMS has established procedures by which students evaluate faculty. As of 2019, every UMS university employs an electronic means of distributing, collecting, and routing student evaluations of teaching.

Faculty recruitment and retention

UMS adheres to an open and orderly process for recruiting and appointing faculty. Faculty and staff—and in some cases, students— participate in faculty searches. The various documents that outline hiring processes through the UMS job search database (HireTouch) are housed on the UMS Human Resources site and on university HR sites.

As noted in Standard Five— and in alignment with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and its own DEI goals— UMS does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender expression, national origin, citizenship status, age, disability, genetic information, or veterans status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. Each university provides reasonable accommodations to persons with disabilities upon request. UMS Human Resources guidelines require

EEO and implicit bias training. OHR provides prospective hires with a written agreement describing the nature and term of the position they are being offered.

| Faculty | Full-time (1,061) | Part-time (1,288) | Total (2,349) |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Indian/Alaska Native (10) | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0% |

| Asian (87) | 6.1% | 1.7% | 4% |

| Black/African American (25) | 1.4% | 0.8% | 1% |

| Hispanic/Latino (46) | 2.6% | 1.4% | 2% |

| Multiracial (17) | 0.9% | 0.5% | 1% |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific (1) | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0% |

| White (1,822) | 83.3% | 72.8% | 78% |

| Not Specified (342) | 5.0% | 22.4% | 15% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Faculty salaries vary across UMS, based in part on the nature a given university’s mission, its balance of teaching and research, the area of Maine it is principally located in (which affects cost of living), and rank (or role/classification). There is no standard means of tracking job satisfaction across UMS. Individual universities compile such data— e.g. UM’s 2018 work-life balance report— but there is no System-wide equivalent.

All UMS universities have dedicated funds for continued professional development, including in-house research grants, sabbaticals, and funds for travel to professional conferences. The universities have various models in place for supporting faculty grant writing and research, and professional development can be funded externally as well as internally. Resources vary based on the size of the university, the balance of teaching and research, the history of bequests, and the extent of grant-writing resources.

Policies at the UMS and university levels define faculty responsibilities and criteria for professional advancement. The faculty union handbooks lay out criteria for recruitment, appointment, retention, evaluations, promotion, and, as applicable, tenure. The most recent union handbooks are available in digital form on the UMS website.

In addition, UMS universities have faculty handbooks outlining policies specific to each. These also include responsibilities of full-time and part-time faculty, dispute resolution procedures, the organization of governance bodies, procedures for the assessment of teaching, ethical guidelines, and other matters controlled by the individual universities.

Teaching

Teaching at the seven UMS universities and the University of Maine School of Law (Law School) is undertaken by credentialed, carefully vetted tenure-stream and part-time faculty. Teaching at all levels and in all modalities to all student populations is evaluated through formative and summative assessments. Findings from those assessments are used to improve student learning, courses, and programs.

Each UMS university offers continuing educational experiences to help faculty stay current in their pedagogical practices, including the use of new and emerging teaching technologies. These faculty development opportunities are often organized and led by instructional design staff, such as those housed in UM’s Center for Innovation in Teaching and Learning, UMF’s Teaching and Learning Collaborative, UMPI’s Center for Teaching and Learning, UMA’s Faculty Development Center, and USM’s Center for Collaboration and Development.

Non-credit teaching and outreach courses and programs are delivered primarily through UM Cooperative Extension, which has a physical and staff presence in all sixteen Maine counties. Extension’s programmatic emphases include 4-H, food safety, and community development. Cooperative Extension faculty and staff manage active farms and educational camps throughout Maine, and share their expertise in the blueberry and potato industries and numerous other areas of the Maine economy. As noted on the Institutional Characteristics Form, Cooperative Extension delivers the preponderance of non-credit educational programming and outreach in the state.

UMS faculty direct independent studies, fieldwork, credit-bearing internships, practica, and clinical experiences (often with a credentialed field practitioner), and many participate in multi-university courses, programs, and/or collaborations.

Update on the University of Maine at Farmington’s Seguinland Institute partnership

UMS and UMF submitted a successful substantive change request in September 2021 to establish an agreement with the Seguinland Institute of Georgetown, Maine to offer UMF credit for courses taught through the Institute.

Since that request’s approval, the partnership has been strengthened in several ways. Specifically, UMF has 1) surpassed its fiscal and enrollment targets for the 2021-22 academic year; 2) fully aligned its admissions processes, review of faculty, curricular development, and assessment of student learning outcomes; and 3) used the Seguinland location to deliver high-impact first-year fall seminars.

As part of joint administrative processes between the two institutions, Seguinland’s Executive Director sends UMF’s Associate Provost a summary of new student applications along with Seguinland’s rationale for admission decisions, which are aligned with UMF’s admission criteria. The Associate Provost approves, disapproves, or requests additional information. Similarly, new Seguinland instructors are vetted and approved by UMF consistent with the university’s regular hiring and review criteria. In the case of new courses, Seguinland’s Executive Director seeks initial approval from the appropriate UMF department chair and final approval from the Associate Provost.

Seguinland outputs are encouraging. Student course evaluations conform with UMF’s, and student assessments of faculty for three Seguinland courses taught in fall 2021 were strong. The faculty received scores of 4.8, 4.5, and 4.9 (out of 5.0), respectively. Of the 55 UMF students who attended a Seguinland course, over 90% are still enrolled at or have graduated from UMF, far exceeding the university’s average retention rate. UMF and Seguinland are currently planning a broader longitudinal assessment of student learning outcomes across the full set of Seguinland course offerings.

Update on the University of Maine at Augusta’s graduation goals

The University of Maine at Augusta (UMA) has set a goal of 18% for its overall IPEDS first-time, full-time 150% graduation rates. UMA has had rates of 18%, 19%, 13%, and 16% for its four most recent cohorts. Its one-year retention rate for baccalaureate cohorts continues to climb, rising from 59% for the fall 2017 cohort to 65% for the fall 2020 cohort.

The university recognizes that its overall first-time, full-time students remain a fraction of its total enrollments: 25.8% in the most recent tally. UMA’s Student Achievement Measure (SAM) report shows that its 2014 baccalaureate first-time, full-time students have either graduated from UMA (20%) or from another university (11%), are continuing at UMA (7%) or at another university (11%), and are either successful or continuing on the path of success. According to SAM, the total student success rate of 49% is down slightly from the data UMA reported to the Commission in early 2021 (at 53%), but is a fuller indication of graduation rates and success rates of its student population.

UMA’s efforts to improve student success continue apace. While its Title III Strengthening Institutions Grant ends this year, UMA has completed an Online New Student Orientation and continues to have a higher percentage of students complete an orientation experience, having incentivized that program. UMA has also determined that its Class Stewards program, while producing modest results, is not sustainable. Instead, the university is using the EAB Navigate platform to ask faculty to issue progress reports at the three-week mark— focusing on no-shows and class entry issues— and again at mid-semester (fall and spring).

Over 60% of UMA faculty responded to the fall 2021 Early Progress Report initiative and then submitted 755 at-risk evaluations. Staff conducted outreach to these students. The university has also implemented the Early Alert tool in Navigate allowing faculty to report a student concern at any time. These steps permit more comprehensive monitoring and earlier interventions. In addition, UMA has increased capacity for online student engagement in a variety of student support areas during the pandemic.

Scholarship

Faculty scholarship

Scholarly expectations for faculty vary widely. Consistent across UMS, however, is that the scale of expectations varies with the percentage of each appointment dedicated to research. Faculty at universities with graduate degree programs have higher expectations for research on average than those that do not.

For all UMS universities, the percentage of workload devoted to scholarship or research is defined in the letter of appointment, and Article 10 of the AFUM contract ensures that faculty with mixed appointments (e.g. teaching and research) have total workloads comparable to those with 100% appointments in any one area. Article 10 further ensures that each department, division, or other appropriate academic unit develops evaluation criteria addressing scholarship, course and curricular development, and instruction as appropriate to the unit and the faculty appointment.

Evaluation of faculty

To account for the distinct needs of departments and universities across UMS, evaluation criteria outlined in the contract are calibrated to the mission and goals of each. For example, although the same evaluation criteria are applicable universally, the local focus is more heavily trained on teaching at UMM, UMA, and UMF as compared to UM.

Consistency in the quality of faculty performance is addressed in university-wide peer evaluation, promotion, and tenure processes and in AFUM-required student evaluations of teaching. Evaluation procedures and review timelines for full-time tenure-track and non- tenure-track faculty are well-established and follow annual cycles.

Part-time faculty are evaluated against criteria, timelines, and procedures outlined in the PATFA contract and rely on student and peer evaluations. Evaluation and reporting for part- time faculty are difficult to track comprehensively. Recent improvements in the onboarding of part-time faculty via the Hire Touch software platform should lead to improvements in processes for hiring, orienting, tracking, and evaluating part-time faculty, and will be assessed in that regard.

Academic freedom

Under Maine law, UMS faculty enjoy traditional academic freedoms in teaching, research, and expression of opinions, and are to be consulted in the formulation of academic policies. All UMS universities have faculty senates or assemblies— and in some cases, a staff senate or assembly engaged in university-level shared governance. These university- specific bodies have primary responsibility for the content, quality, and effectiveness of curriculum offered fully by that university, and the protection and fostering of the academic freedom of all faculty.

The relevant UMS policy statement is Section 212 of the Board’s policy manual. Article 2 of the AFUM contract and Article 3 of the PATFA contract addresses academic freedom. These documents affirm the rights of free inquiry in the performance of teaching, research, publishing, and service obligations. All UMS universities also have faculty handbooks and faculty senate/assembly bylaws that define and affirm academic freedom. All recognize the necessity of academic freedom in higher education and commit to guaranteeing its unfettered exercise.

Each UMS university’s administration is responsible for enforcing academic freedom policy in accordance with System-wide policies and standards, and protecting individual rights through adequate and timely review of alleged violations.

Assessment and pedagogical effectiveness

Each university engages in its own institutional assessment through systems of reports, surveys, program reviews, and program accreditation processes supporting continuous improvement. For example, in 2020 USM’s Office of Academic Advising undertook a NACADA/Gardner Institute assessment process leading to a gap analysis and development of a strategic plan for academic advising.

Content and methods of instruction are assessed in a range of ways. The program review process requires academic programs to evaluate their courses on a cyclical basis: generally, every five to seven years. For example, USM’s program review principles include consideration of the role of the program in the context of the mission and goals of the university, and require that program reviews be used as the basis for the improvement of outcomes and the identification of future goals. In addition, many programs across UMS yoke learning outcomes to the standards of their professional organizations (e.g. the American Psychological Association for psychology programs).

Individual courses are also evaluated for content and methods of instruction through annual program assessments and institutional-level evaluation of general education learning outcomes. In addition, university-level general education program outcomes provide valuable information to programs whose courses are part of the program. The effectiveness of instruction is regularly and systematically assessed at all universities through peer evaluation of content and methods of instruction during reappointments and related peer reviews (e.g. tenure or post-tenure reviews).

Curricular innovation

UMS universities encourage curricular experimentation. At UMA, for example, courses can carry an “E” (experimental) designation permitting expedited approval as warranted by need or opportunity. At other universities and at the Law School, initial and/or experimental courses are generally classed as topical or “special” and are offered at the discretion of instructors and program directors.

UMF’s Innovation Agreement promotes experimentation by allowing faculty to request that course evaluations during the initial offering or implementation of a course be framed in the context of pedagogical experimentation. The spirit of this agreement is to ensure that faculty do not to have to worry about being penalized for trying something new.

The experience of UMS universities with COVID-19 provides evidence of curricular nimbleness, responsiveness to student needs, and the ability to adopt alternative instructional approaches while preserving academic quality. Between March 9 and March 25, 2020, UMS faculty worked to ensure that several thousand course sections would be available to all students remotely. IT deployed its resources, the various centers for teaching and learning partnered to support hundreds of faculty, and UMS and university leaders worked together in implementing a massive shift in instructional delivery to serve our students.

Campus alignment and differentiation

UMS programmatic offerings collectively align with its multifaceted mission. Survey courses serving as prerequisites in degree pathways are offered across UMS. For example, mathematics, English, and biology courses are offered at all seven universities. Each university offers mission-relevant courses and programs. Examples include UMFK’s rural public safety administration program, UMM’s book arts certificate, the Law School’s environmental and ocean law certificate, and UMA’s aviation program.

Students in each major are taught by a variety of faculty to provide exposure to different academic strengths and viewpoints. An appropriate balance between flexibility and consistency in learning outcomes is promoted (where feasible) through delivery of multiple sections of the same course, thereby exposing students to a range of faculty expertise and teaching styles.

There are also mission-linked differences across UMS in educational philosophy. For example, the 2021 UMF strategic plan includes a strong emphasis on providing students a full array of experiential learning opportunities, while UM graduate students play an important role in undergraduate education, and both undergraduate and graduate students are deeply involved in the university’s research mission.

UMS universities offer first-year experiences aligned to their respective missions. For example, the First Year Seminar (FYS) is an integral component of the overall first-year experience at UMF. Its twin purposes are to help students make a successful transition to college and develop habits of lifelong learning. In summer 2019, UMF piloted a version of FYS dubbed First-Year Fusion that includes a week of high-impact experiential learning prior to fall orientation, and ends in mid-semester to allow students to turn their focus to their remaining (regular) courses.

Advising

Advising models vary by university and sometimes by program. At some universities, advising reports to Academic Affairs, as it does at USM and UMA, and in others it reports to Academic Support Services, as it does at UMFK. UM has a college-level advising model: some UM colleges have designated advising centers and staff, while in others faculty take on the advising role.

Most UMS universities provide both professional and faculty advisors to students (e.g. UMFK, UM, UMA, the Maine Law School, and UMPI). UMF is rethinking its advising model via its Advising Futures Committee, and USM is developing a new strategic plan for academic advising. Advising is part of full-time faculty members’ duties and is evaluated during promotion and tenure review.

Appraisal

Workload considerations

Workload expectations for full-time faculty are adjusted as needed. Often this is done at the individual level— or example, faculty may be given a course release to take on administrative work— or it may be done (more rarely) on an institutional level. There is no standard process for reappraising faculty workload, an issue that grew in importance in 2020-21 when the pandemic struck and faculty had to learn new modalities of teaching immediately. This this has not been figured into faculty workload remains a challenge. In addition, growing enrollment and shifting enrollment caps are sometimes not accounted for in evaluating workload.

All UMS universities employ sizable contingents of adjunct and non-tenure-track faculty whose primary responsibility is teaching, and who often bring particular skills into the classroom. At the Law School, for example, these instructors are typically practicing attorneys who incorporate their legal work into their teaching. University and Law School adjunct and non-tenure-track faculty often also work in unofficial capacities, advising students and taking part in program assessment. This is typically work for which they are not additionally compensated.

Variable workload definitions (e.g. 4/4; 4/3; contact hours; credit hours) make comparisons of positions and compensation across UMS difficult. Meaningful assessment of workloads means establishing common definitions of teaching loads, variable positions, and tracks, and accounting for teaching done at a university other than a faculty member’s home university (for example, in a course or program delivered jointly by multiple UMS universities).

Update on the University of Maine at Farmington’s four- to three-credit conversion

In 2021, UMF began converting from a largely four-credit to a largely three-credit curriculum, and from 128 to 120 hours required to earn a degree. These moves followed rigorous review through a campus strategic planning process, two external studies by Hanover Research, and completion of an external report in March 2021. The report reflected outputs from numerous meetings with the President’s Cabinet, Faculty Senate, Academic Leadership Council (a mix of faculty and administrators), and a faculty working group, as well as multiple open campus sessions.

In revising its curriculum, UMF anticipates significant benefits to students and the university, including:

- greater curricular alignment with the rest of UMS

- increased opportunities for shared programming and instruction

- improved curricular efficiency

- markedly reduced barriers for transfer students

- overall reduction in the cost of a UMF

Considerable work on the four-to-three conversion has been done over the past year and will continue through summer and fall 2022. A planned implementation in fall 2023 requires that most curricular changes be made by the end of fall 2022.

In January 2022, every UMF academic division submitted complete drafts of proposed program revisions for the university’s approximately 90 undergraduate major, minors, and certificates. Proposals were reviewed by the UMF leadership and returned with feedback along with requests for information about course cycling and capacity to deliver programs with existing faculty.

By April 2022, the majority of UMF programs had submitted catalogue-ready program and course descriptions. (Education programs will not be submitted until September 2022 as UMF awaits final word of state teacher certification requirements.) Three-fourths of UMF’s remaining programs have been reviewed by the leadership; a quarter have been approved by the relevant division and the leadership and are under review with the UMF Curriculum Committee and Faculty Senate.

Update on the University of Maine’s progress in strengthening its funding model for research and increasing research funding and doctoral education

UM has pursued several initiatives in the past two years to stabilize and strengthen the funding model for research and increase research funding and doctoral education. These efforts are described below. Investments are included in multi-year planning assumptions for the research and graduate school enterprises.

Strengthening the funding model for research

To further develop the funding model for research, an F&A distribution model was approved by the university in November 2020. While for the previous four years UM applied an F&A distribution model that only supported PIs, the new model for the first time also directly returns a fraction of F&A funding to the units supporting the research that generated the funds. The new model is designed to incentivize and support faculty and academic units in the growth and advancement of their research efforts while also covering for increased expenses resulting from the growth.

Due to concerns about the pandemic causing a possible budgetary shortfall, UM postponed the implementation of the new F&A distribution model by one year. (Two elements of the new model were considered in fiscal year 2022: an improved distribution model for PIs, and second-year implementation for UM’s largest research center, the Advanced Structures and Composites Center).

Beginning in fiscal year 2022, UM has provided one million in base-budgeted funds to the Office of the Vice President for Research and Dean of the Graduate School to address urgent needs arising from the growth of the research enterprise, with additional base funds under consideration for fiscal year 2023 and beyond for new-faculty cluster hiring to support UM’s continued success in securing extramural funds.

Increasing research funding

In fiscal year 2021, despite challenges posed by COVID-19, UM set a new record by generating $133.6 million in external funding in support of research and development activities as compared to $56.9 million in fiscal year 2017: a 135% increase over that five- year period.

R&D expenditures also reached a new all-time record of $179.3 million in fiscal year 2021 as compared to $99.5 million in fiscal year 2017, an increase of 80.2% over the five-year period. UM is committed to sustaining this effort, and doing so will require new funding models and other improvements. Moreover, as the growth and development of the research enterprise has accelerated, the university recognizes that it needs to move more of its research enterprise to base-budget funding. This process began in fiscal year 2022 as highlighted below.

UMS and UM have increasingly raised visibility among policymakers about the connection between UMS R&D activity and talent development and economic growth. Throughout the pandemic, UMS hosted biweekly virtual briefings for legislators and congressional staff spotlighting university research and researchers contributing to pandemic response efforts, including in support of public health, K-12 education, and small business development.

Further, university leaders have assumed leadership roles in numerous statewide planning efforts, including the creation of a 10-year state economic strategy and plans on climate action and economic recovery, all of which included bold increases in public R&D investment among their priority recommendations.

UM avails its resources, labs and related facilities, and staff to work with business and industry for joint R&D and problem-solving as well as programs for business and technology acceleration and incubation. The highest volume of contract work occurs in UM research centers, including the Advanced Structures and Composites Center, the Forest Bioproducts Research Institute and Process Development Center, the Advanced Manufacturing, and the Aquaculture Research Institute.

In the last five years, UM has focused on growth in the industry contract and technology commercialization space, with outreach and education/training activities including TopGun entrepreneurship training program, the Maine Innovation Research Technology Accelerator (MIRTA), an NSF I-Corp program, and a Commercialization Series workshop for faculty, staff, and graduate students.

UM operates three incubators supporting startups and spinoffs. The patent portfolio is growing in the areas of renewable energy, bioproducts, computer-aided medical diagnostics, neutriceuticals, and advanced manufacturing, with licensees pursuing commercialization. The maturing of some of these technologies and market growth opportunities in green technologies hold promise for increased licensing revenue. UM also plans expansions in facilities, labs, and equipment to modernize and support large- scale additive manufacturing of biomaterials, advanced manufacturing and automation, biomaterials for medical applications, aquaculture, precision agriculture, and food innovation.

Growth and expansion in research and graduate studies, coupled with a growing level of support for research and graduate studies made available to other UMS universities, means there is a need for more investments in research infrastructure and resources for UM to sustain these efforts while also maintaining its own activity. UM is exploring how increases in revenues generated by the growth in research and graduate studies in combination with UMS Research Reinvestment Funds (RRF) can be allocated to meet increased demands for services and known needs to sustain and maintain research and graduate studies growth. (In 2015, UMS made a recurring $2.1 million in administrative review savings available for a multi-year research and economic development initiative to create RRF. UM administers these funds to support the growth and development of research and development efforts at UM and across UMS.)

Budget planning is in development to support the necessary UM research-related resources, including for the Graduate School, the Offices of Research Development, Research Administration, and Research Compliance; Advanced Research Computing, Security, and Information Management; CORE Facilities; and the Office of the Vice President for Innovation and Economic Development.

An incentive-based proposal to share up to 60% of the incremental net revenue from new entrepreneurial programs is moving toward implementation. Entrepreneurial and innovative activities at the UM contribute to its teaching, research, and service missions directly (by providing educational opportunities in new or emerging fields) and indirectly (by providing funds to enhance scholarly research, creative activity, innovation, and training). The purpose of the entrepreneurial funding program is to encourage and incentivize academic units to develop graduate programs that can meet the needs of targeted new audiences and generate new sources of revenue.

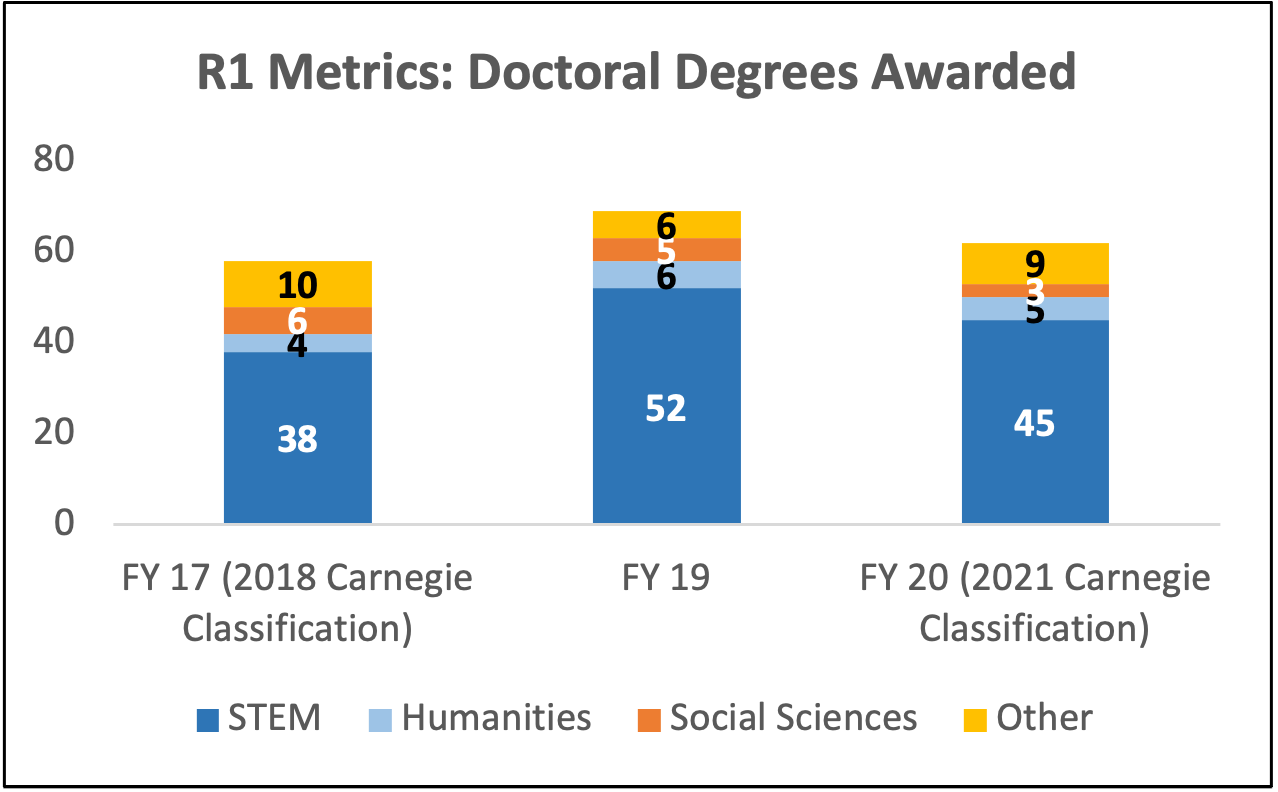

Increasing doctoral-level education

In spring 2021, total UM doctoral enrollment exceeded 500, and in fall 2021 overall graduate student enrollment and doctoral student enrollment reached all time highs at 2,557 and 522, respectively. Graduate assistantship stipends have been increased to recruit and retain high quality students, and more will be done to reach levels reflecting the stipends provided at other New England flagship universities. $500,000 increases in the Graduate School budget to fund recruitment, assistantship stipends and other personnel are included in multi-year planning projections.

In March 2021, Chancellor Malloy invited UM President Ferrini-Mundy to assume an additional responsibility as UMS Vice Chancellor for Research and Innovation, with an expectation of increasing research engagement across the System. In the long term, this may result in increased revenues for the UM research and doctoral education enterprise through expanded submission of proposals to federal sponsors by faculty across UMS, and the prospect of shared F&A.

The recently launched UMS Faculty Affiliates program helps facilitate research collaborations between UM faculty and their colleagues at other UMS universities and the Law School. The program also supports the growth of graduate education by providing enhanced teaching experiences for UM graduate students who aspire to careers in the academy as they teach classes for UMS faculty on research sabbaticals or related research- time protections.

The Faculty Affiliates program is also expected to aid in UMS’s response to an issue described in the June 2020 substantive change request. Introducing faculty from other UMS universities to research collaborations at UM will likely influence future curriculum at those universities and thereby expose their students to courses and programs otherwise inaccessible to them.

The 2020-2024 UMS research and development plan articulates goals through which research can be expanded across UMS, with RRF as a key catalyst. The R&D plan aligns with UMS efforts to support implementation of the state’s 2020-2029 economic development strategy— emphasizing talent and innovation— and with NECHE’s July 2020 letter to UMS affirming the need to strengthen the funding model for research and increase research funding and doctoral education at UM.

Projection

Guidance for multi-university academic programs and their faculty

As UMS moves to a more unified approach to teaching and learning, it will need to disseminate standardized guidance for multi-university academic programs and related collaborations. It will also need to consider the impact of cost-sharing agreements, provide seamless academic processes (e.g. course registration, financial aid flow) for multi- university students, and support faculty innovation.

Programmatic review of learning outcomes

To assess student learning, academic programs at all universities engage in learning outcome assessments that are typically presented in programmatic annual reports.

UMS universities will engage faculty more fully in the programmatic review of learning outcomes. Faculty are appropriately engaged at the course and program levels already, but lack a system to quantify how students are meeting program learning outcomes. Relatedly, the assessment work faculty are already doing should be acknowledged and formalized.